It’s on. Not a nuclear conflict on the Korean Peninsula, thank goodness. But an old-fashioned, trash-talking smackdown between two nuclear-armed adversaries. In the one corner, we have US President Donald Trump, verbal pugilist and reluctant leader of the free world. In the other corner, there’s North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, the 33-year-old heir to the world’s only communist dynasty.

The insults have been flying. Trump has derided Kim as “Little Rocket Man” and a “madman” and he threatened to “destroy North Korea”.

Kim retorted that Trump was “a frightened dog” and a “mentally deranged US dotard” and he vowed to continue building his missile arsenal. Kim’s foreign minister took it a step further, calling Trump’s tweets “an act of war”.

We all know by now that Trump has been the purveyor of the put-down since he first entered the political arena. He rode his name-calling, art-of-the-insult campaign all the way to the White House, dispatching opponents like “Lying Ted” Cruz, “Little Marco” Rubio, and, of course, “Crooked Hillary” Clinton.

Can Trump do anything to stop a war with North Korea?

But while his rhetoric may be more extreme, Trump is actually just following a long line of American presidents who have repeatedly shown a dangerous tendency to personalise foreign policy disputes, resort to childish taunts, and naively assume that countries with long histories and complex cultures can be reduced to the exigencies and eccentricities of their leader of the moment.

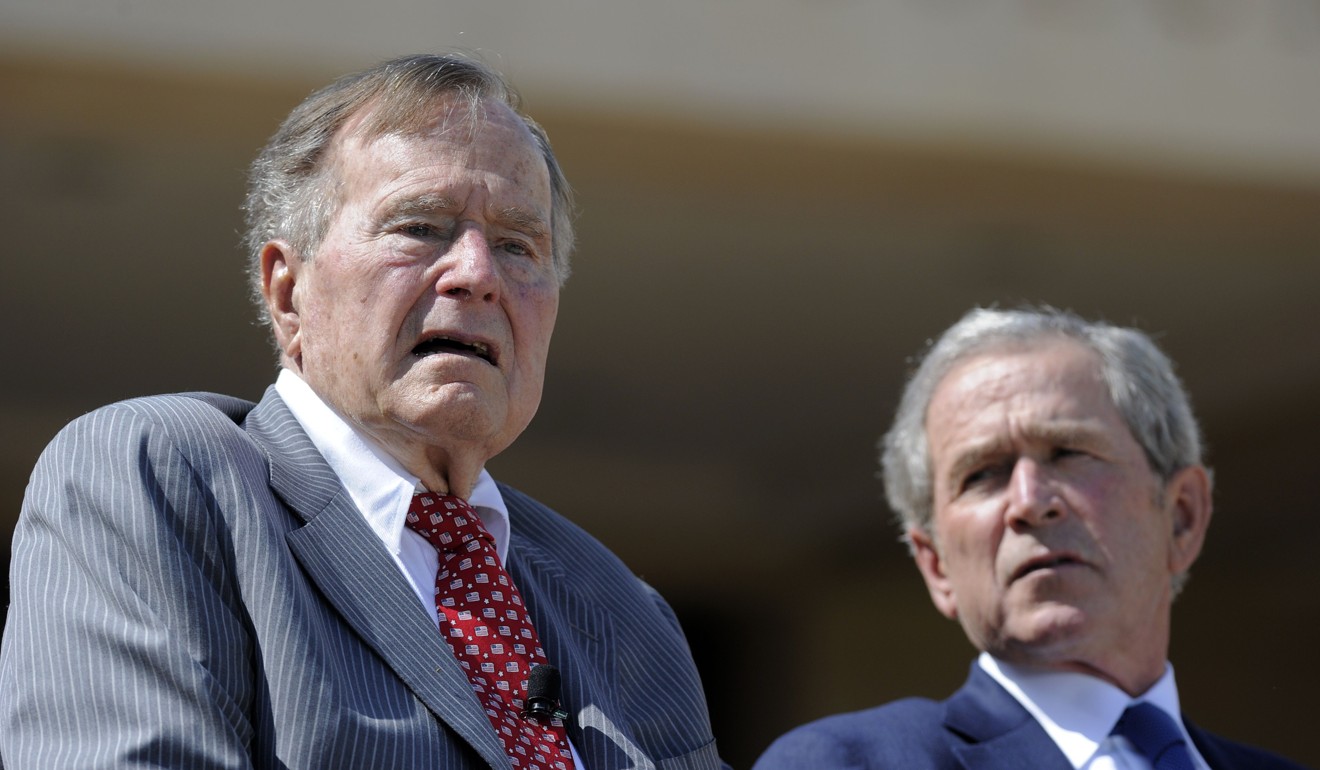

So it was, for example, during the Contra war in Nicaragua in the late 1980s, President George H.W. Bush denigrated the Sandinista leader, President Daniel Ortega, as “shameful”, “outrageous” and, in what he envisioned his most demeaning put-down, “that little man”.

When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, Bush also had choice words for him, calling him “a homicidal dictator” and “a little Hitler”. Bush’s son, President George W. Bush, went further, mispronouncing the Iraqi leader’s name as “Sa-dam” – to rhyme with “Adam” – which in Arabic roughly translates into “little shoe shine boy”.

The Hitler comparison is also the most vastly overused. During the Balkans war in the 1990s, vice-president Al Gore referred to Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic as “one of these junior league Hitler types”.

We – and here I include us in the news media – like to divide the world into good and evil, personified by enemies and icons.

The enemies are irreparably villainous, cruel, murderous, power hungry and slightly insane, and they appear on the cover of Time magazine looking particularly sinister.

The icons are beyond saintly, moral beacons of steadfast determination and justice – until they aren’t, and they lose their halos and fall from grace.

Vladimir Putin is routinely depicted as an evil mastermind bent on murdering all opponents, destabilising the globe and undermining the West. Raul Castro is ruthless and corrupt. Nicolas Maduro is a thug clinging violently to power. The shorthand version becomes “Putin’s Russia”, “Castro’s Cuba”, or “Maduro’s Venezuela”. And, of course, “Xi Jinping’s China.”

Trump’s nuclear stand-off with North Korea: why this is no Cuban Missile crisis

The icons fare little better in this incessant personalisation of policy. Witness the rise and fall of Myanmar’s Aung San Suu Kyi. During her decade and a half of house arrest, the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize, her release in 2010, and her victory in Burma’s first free election in a generation, Suu Kyi could do no wrong. She was the steely eyed symbol of her country’s democratic aspirations, the petite woman who stared down Burma’s generals and won. She was lauded with a visit to the White House and awarded the Congressional Gold Medal.

Now, because of her silence over the violence and mass expulsions directed at the country’s minority Rohingya Muslims, Suu Kyi has been roundly criticised, with 22 members of Congress calling for her to take a stronger stance and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman saying the icon risked “destroying her reputation”. That steely determination suddenly became stubbornness.

I have seen it before. When Corazon Aquino led the 1986 “People Power” revolution that toppled the Ferdinand Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines, she was revered as nothing less than saintly. But when Aquino left office in 1992, amid mass electricity shortages and having failed to address the country’s endemic poverty, to tame the restive military or reform its unequal distribution of land, the once-flawless icon was considered an inexperienced and ineffectual housewife unsuited for the presidency. The same goes for Indonesia’s Megawati Sukarnoputri.

Why sanctions will only fuel North Korea’s missile tests

When we make leaders the personification of their countries, and then personalise foreign policy, we are given to faulty analysis and misjudgments – sometimes with tragic results. When I drove a rental car into southern Iraq from Kuwait at the start of the 2003 American invasion, it was widely assumed that with Saddam toppled from power, the system he created would evaporate and the Americans would be cheered as “liberators”. Instead, I and my travelling companion found ourselves pinned down by sniper fire from the remnants of Saddam’s Baathist loyalists, evading armed looters and besieged by angry Iraqi civilians demanding to know what we, the invaders, had brought for them.

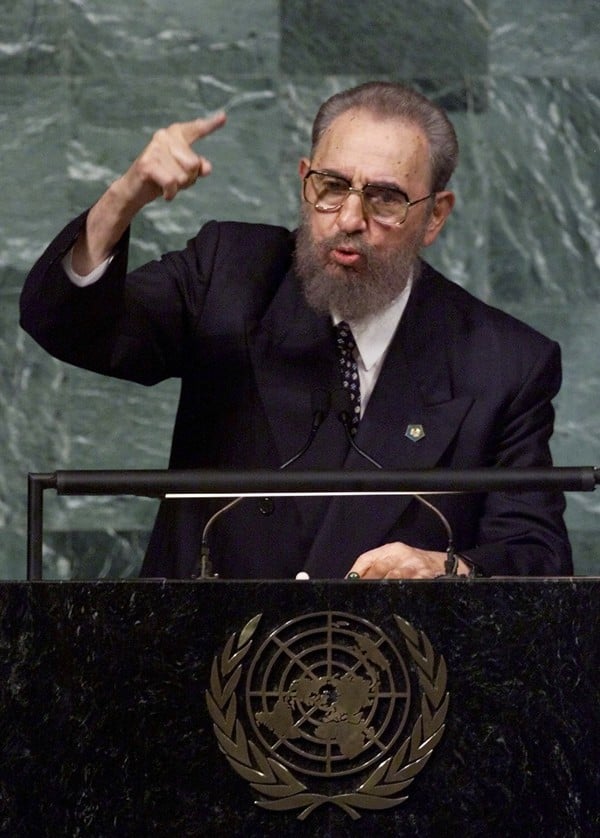

It was assumed Cuba’s communist system would never outlast its revolutionary hero, Fidel Castro. Castro retired from public life in 2008, died eight years later, and his brother Raul Castro took over – and the Cuban system looks as firmly in place as ever. Likewise, in Venezuela; Hugo Chavez is gone, but Maduro so far is keeping the Chavista revolution in power, despite mounting opposition and a crippled economy.

Which brings us back to North Korea. Among the supposed military options under consideration by the United States and South Korea is a so-called decapitation strike, otherwise known as regime change, aimed at taking out Kim and his close cohorts. The assumption is that with Kim gone, the regime would collapse, the army would defect, the people would be freed and North Korea would peacefully reunite with the South.

But what if Kim’s North Korea could survive without Kim? What if the regime not only survives the decapitation, but decides to massively retaliate, with Seoul and Tokyo within missile range? In other words, what if Kim is not just the personification of his country, but its reflection?

It would help if the US administration developed a true containment policy to deal with North Korea as a de facto nuclear power. It needs to abandon a “regime change” policy predicated on Kim being an irrational madman singularly leading his 25 million citizens unwillingly on a suicide mission.

It just might be possible that North Korea is more than just its leader, Kim Jong-un. After all, I like to think the US is more than just its erratic, trash-talking president, Donald Trump.

Original link: https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/2113445/trump-vs-rocket-man-what-if-north-korea-problem-not-kim