Should the Hong Kong government register journalists and issue them an official press card?

This question of journalist accreditation was first broached by police officials who complained that some Hong Kong protesters were posing as reporters, with yellow vests and helmets falsely labelled, “PRESS.” They complained the riot police had no way to tell real working reporters from those they deemed “fake journalists.”

Journalist organisations, media outlets and journalism educators sounded the alarm, warning that any accreditation system was likely to be abused, handing the government to power to decide who was a real journalist and who was not. Chief Executive Carrie Lam was pressed to make a statement on October 19 denying any plans for a centralised registration system.

But Lam also said she had no plans to withdraw the ill-conceived, much despised China extradition bill—a few weeks before she withdrew it. So her statement saying there were “no plans” has been met with suspicion.

Proponents of a press accreditation system say legitimate journalists have no cause for concern, since the practice is common in many other countries, around the region and in many Western democracies. That much is true.

When I landed in Manila for my first foreign posting as a bureau chief for The Washington Post, I was issued a colourful yellow and blue press card that allowed me to enter Malacañang presidential palace, the foreign ministry, and the Philippine military headquarters in Quezon City. Traveling anywhere in the country, that press card opened doors—governors, mayors, provincial warlords, local military commanders and even Communist rebels and army mutineers all recognised the press card and gave me access and interviews. France had a journalist card issued annually by a section of the French foreign ministry. It was a straightforward affair—I brought a letter from the home office, and was handed this card with my photo and the French tricolour, that allowed me to stroll into the Élysée Palace or cross police lines during any protest march. One added benefit; reporters with a valid press card could enter any national museum without charge—and not just in France, throughout the European Union.

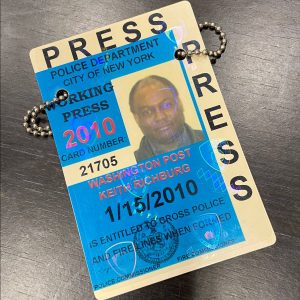

The most convenient press card I had was also one of the hardest to obtain—the New York Police Department press pass. With the NYPD card, I could enter police headquarters easily, I could talk to the cops on the streets, and during crime scenes I could enter into the cordoned off areas behind the yellow “Do Not Cross” tape. To get the card, renewed annually, I just had to show I had written at least three stories involving the NYPD in the previous 12 months—which meant a spate of cop stories in the Post every December.

The difference in all those countries was that the press card was issued to facilitate access and reporting—not to cull the number of journalists. One difference now is that recent years have seen an explosion in the number of journalists—not just those working for major newspapers, like I was. Now the media landscape is populated by freelancers, citizen journalists, part-time bloggers and tweeters, reporters and photographers for startup websites, and recently graduated journalism students still trying to sell their first story or picture. Why should anyone—let alone a government official—tell them they are not “real” journalists?

For me, official press cards over the years actually opened doors and made my job easier. In Hong Kong, in the current atmosphere of distrust of the government and the police, there is a real fear a press card will become a tool of control.

If you think that won’t happen, just look north to China, one of the world’s most restrictive places in the world for the press, ranking 177 out of 180 countries. There, the accreditation system is routinely used to harass and intimidate foreign correspondents. Write something the Chinese Communist Party dislikes, and officials will delay your accreditation, often by months, or dangle the threat of revoking your press credentials altogether—as they did most recently with Wall Street Journal Beijing reporter Chun Han Wong, and many others in the past.

In the past, I might have said a press accreditation system in Hong Kong was worth considering. But in the current situation, it would likely become another step in the gradual erosion of press freedom.

Keith Richburg

Director of the JMSC