October 9 2018

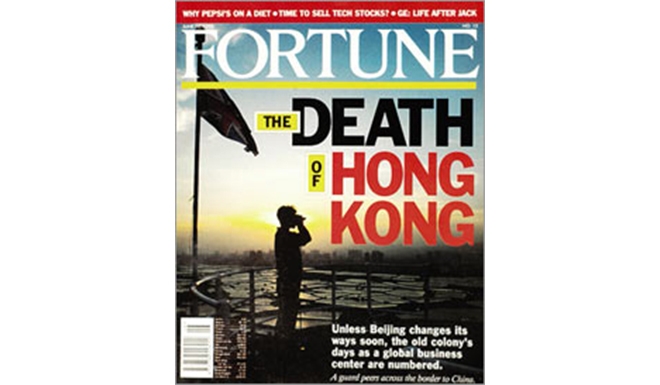

Some future historian writing a thesis on “The Death of Hong Kong” may stumble across the old 1995 Fortune Magazine cover of the same name. It may seem prescient, but premature. Instead, the late summer and early fall of 2018 will likely be deemed the turning point, when the demise of a once-great open and liberal city really began.

That turning point started in July, when local police served notice on the Hong Kong National Party that it was considering a ban, accusing the obscure group of sedition — the first proposed banning of a political party since the territory’s return to Chinese sovereignty in 1997. It ended in October, when the Hong Kong government for the first time in memory effectively expelled a foreign journalist from its soil, by not renewing his work visa.

I’ve been a foreign correspondent covering East Asia for a period spanning 30 years, most of that time for The Washington Post. I was banned from Indonesia for two years, for writing that President Suharto had taken power in a coup. I was barred from Burma, now called Myanmar, for two decades, after slipping into Rangoon in 1989 and interviewing Aung San Suu Kyi.

Never would I have imagined that one day Hong Kong would be expelling a foreign correspondent

And while based in Hong Kong and later in China, I worked tirelessly, having endless lunch and dinner meetings with foreign ministry officials, trying to get journalist working visas for two separate Washington Post correspondents who had been previously expelled and were trying to get back.

Banning journalists was a common practice then. But in all those years, never would I have imagined that one day Hong Kong would be expelling a foreign correspondent.

Hong Kong was always one of the most open places in Asia for a journalist to live, work and cover the region. It’s why so many foreign news agencies made Hong Kong their regional hub. You could fly in and out, it was convenient and it was no hassle.

When I was banned from Indonesia, it was under the Suharto military-backed dictatorship. Burma was also one of the most entrenched military regimes in the world, and they kept out prying foreign reporters as a matter of course. China was always known to tightly restrict entry for reporters, and correspondents had to endure an agonizing yearly ritual each December, waiting to see if their working visa would be renewed.

But Hong Kong for many years always stood apart – until now.

When I asked about getting a local press card, he gave me a bemused smile and told me there was no such thing. “We have freedom of the press here.”

When I first moved here, in January 1995, to set up a new Washington Post bureau, the director of the Government Information Office invited me and a handful of other newly arrived correspondents for lunch. When I asked about the process for getting a local press card, he gave me a bemused smile and told me there was no such thing. “We have freedom of the press here,” he said.

I thought about those days when I heard the news that the Financial Times Asia news editor, Victor Mallet, was being denied a working visa. It was a tactic borrowed directly from the mainland, which used the journalist visa as a means of control.

But in Mallet’s case, the expulsion is actually far worse, since he apparently is not being barred from Hong Kong for anything he wrote. Rather, his “crime” seems to be having been acting president of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club when it defied Beijing’s warnings and hosted a perfectly legal luncheon talk by a pro-independence political activist who authorities consider a threat.

Consider the irony: the Asia news editor, responsible for regional coverage, summarily ejected and given seven days to pack, from what we once all considered the free press hub of Asia.

Why would Hong Kong authorities — or, more likely, Beijing’s leaders — take such a dramatic step, to undermine the city’s status as a bastion of free speech? There’s the old Chinese saying, “kill the chicken to scare the monkey.” By denying a visa to one correspondent, it puts the rest on notice that the regime here has changed, critical reporting will not be tolerated and it’s best to toe the line or pack up and leave.

Except there are few places to leave to, in a region notoriously inhospitable to foreign reporters. Most will stay, and I fear they will become more circumspect in what they write and say, exercising self-censorship out of concern for also being expelled. The chicken has been slain. The monkeys have taken note.

Keith Richburg is director of The University of Hong Kong’s Journalism and Media Studies Centre. He was a long-time Washington Post correspondent and foreign editor, and he was president of the FCC during the 1997 handover of Hong Kong from the UK to China.

Original link: https://www.inkstonenews.com/opinion/keith-richburg-expelling-foreign-correspondent-marks-beginning-hong-kongs-demise/article/2167594