Exactly two decades ago, at the beginning of July, 1997, Asia was shaken by a seismic event that upended the established order and sent ripple effects still reverberating across the region even today.

No, I am not talking about Hong Kong’s handover to China; by comparison, that was largely a non-event, carefully planned and entirely scripted. I am speaking of the unplanned and unexpected shock that was far more consequential to millions of people – the Asian economic crisis that began on July 2, 1997.

The financial meltdown lasted more than three years, roiled the regions’ politics, collapsed living standards and overturned a generation’s worth of growth. Twenty years later, its impact continues to be felt.

Umbrellas now and then: 20 years since Hong Kong handover, have things really changed?

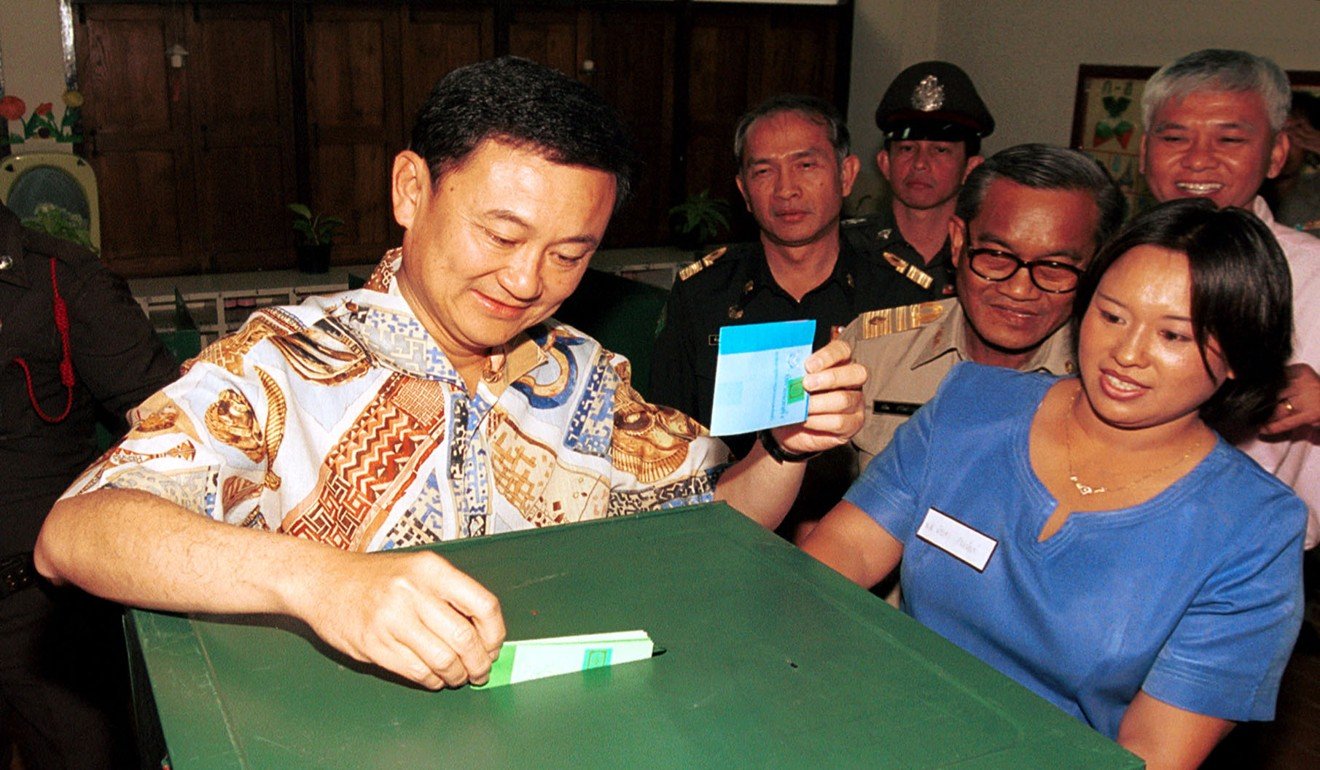

In Indonesia, President Suharto’s 30-year-long “New Order” regime was overthrown, the long-time dictatorship was replaced with a boisterous democracy; East Timor broke away and became an independent country. In Malaysia, the crisis led to a split in the ruling United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) party with the sacking of the deputy prime minister and finance minister, Anwar Ibrahim, and the start of the reformasi (reform) opposition movement. In Bangkok, Thais took to the streets demanding a new “people’s constitution” that paved the way for the 2001 landslide victory by tycoon Thaksin Shinawatra and his “red shirt” loyalists. Thaksin’s controversial tenure, and his eventual overthrow by the military, form the main fault line in Thai society today.

Hong Kong also faced a speculative attack on its currency. But the monetary authority, sitting on a massive pile of reserve cash, spent more than US$1 billion to support the US dollar peg. When the speculators turned to the stock market, Hong Kong officials reacted swiftly, buying up shares of targeted companies. When the government eventually sold its shares two years later, it turned a tidy profit. Donald Tsang, the finance chief, was hailed as a hero. Many Southeast Asian countries saw how easily Hong Kong, with its US$80 billion in foreign exchange reserves, beat back the currency speculators, and they resolved to build up their own cash reserve stockpiles. The result is a huge official savings level in Asia today, while the US piles up large deficits.

Hong Kong handover: what we got right (and wrong) in predictions for 2017

Some economists trace a direct line from the 1997 crisis in Asia to the 2008 financial collapse that began in the US and spread across most of the world. One side effect was that as Asian countries began building up huge foreign exchange reserves, they began to stockpile US Treasury Securities. That led to over-borrowing in the US and the low interest rates that contributed to the 2008 financial crisis.

Asia eventually recovered from 1997 – thanks to a series of bailout packages from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – and most of the countries emerged stronger. But the IMF rescue came with strict conditions attached, including demands to slash government spending and open their economies to foreign competition. The humiliating rescue left a lingering anti-Western sentiment and a distrust of the global financial institutions.

But when the crisis first hit, most international journalists, myself included, were too fixated on the end of British colonial rule in Hong Kong to notice. We worried about the dangers of what might happen here, and largely missed the real crisis unfolding before us.

What worried us was the prospect of one of the world’s freest capitalist cities being taken over by a brutish Communist regime that only eight years earlier had cracked down on students at Tiananmen Square. We feared the People’s Liberation Army troops would march down Nathan Road slaughtering pro-democracy demonstrators. We feared outspoken liberal politicians would be jailed, that newspapers would be cowed or shut down, and that those locals lucky enough to have foreign passports would begin fleeing in droves. Then Hong Kong would become just another mainland Chinese city.

Of course none of that was predestined. Previous agreements were supposed to protect Hong Kong’s system, and keep it in place for 50 years. But the handover of sovereignty of a capitalist city to a communist country was something that had never been tried before. And our job, as journalists, was to be vigilant, and sceptical.

Hong Kong did face an immediate crisis after the handover – a brutal slaughter caused by a contagion from the north. But it was an outbreak of bird flu, which killed four people, caused widespread panic and prompted the mass extermination of more than a million chickens.

Bird flu was a big early test of the new government’s ability to manage a crisis, and it was largely judged to have come up short. Skittish local officials here were even reluctant to admit the obvious – that the avian virus likely came from China, the origin of 80 per cent of the city’s live chickens. If combating the currency crisis showed the local government’s deft financial prowess, bird flu showed the opposite – a new administration, unprepared for a major health crisis, and facing a sceptical public and press.

THE BUBBLE BURSTS

It’s hard to exaggerate the devastation the crisis wrought. Within just a few weeks, more than 5 million people lost their jobs in Indonesia, a million more were left unemployed in South Korea, and 2,000 people a day in Thailand were losing their livelihoods. Factories around the region were going bankrupt and shutting their doors. A hospital in Seoul was shut down when it could no longer pay its staff or its bills.

Malaysia’s ringgit rout raises spectres of 1998 Asian Financial Crisis

In Bangkok, laid off stockbrokers and bankers began selling their designer clothes and jewellery at impromptu street markets of the Formerly Rich. Young former professionals were reduced to driving cabs or selling food from roadside carts. Children were dropping out of schools, malnutrition rates began to rise, and migrant workers were returning from the cities to the countryside in a kind of reverse migration.

What was most stunning about the 1997 economic crisis was the fact that it came so soon after a decade of double-digit growth that was so impressive it was uncritically dubbed “the Asian Miracle”. Throughout the 1980s and into the early 1990s, it seemed Asia could do no wrong. The Asian Tigers – Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong and South Korea – were being quickly followed by the Asian Cubs – Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines. It was believed they had found the key to long-term, double-digit growth of 8 per cent to 10 per cent that could last in perpetuity – low taxes, openness to trade and foreign investment, big capital spending on infrastructure, government intervention in key economic sectors and investment in education. And, of course, paternalistic strongman leaders, considered “visionary” nation-builders, like Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew, Indonesia’s Suharto, Malaysia’s Mahathir Mohamad, and the army generals who ran Thailand like Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda and Chavalit Yongchaiyudh.

Western economists and investors swooned. They wrote books about these Asian leaders’ economic brilliance. Seldom mentioned, or largely downplayed, was the fact that these were also authoritarians who trampled over human rights, locked up dissenters and shackled the press in their countries. But the proof of their success was in their high growth rates. Reducing poverty, I was consistently told, was more important than expanding the democratic space.

First 100 days of President Trump: like a drunk stumbling down a highway

Asia’s self-confidence born from the 1980s boom gave way to a sense of superiority which in turn gave way to hubris. And this soon became wrapped in its own over-arching political philosophy called “Asian values”, which was then touted as an alternative to the Western model with its emphasis on democracy, human rights and individual freedom. Argue against it, and Asian leaders would throw their double-digit growth rate right back in your face.

The biggest problem underlying the myth of the Asian miracle was the mountain of bad debt. Much of the 1980s and early 1990s boom was based on inflated property values, and many Asian urban yuppies had jumped into the property market like it was a Macau casino. Banks were lending larger and larger amounts, condo prices and stock values were soaring in Bangkok, Jakarta and Manila, and it seemed the good times would keep on rolling. Until it stopped and the bills came due.

There were early signs of trouble.

The year before the crisis hit, a bank in Thailand called the Bangkok Bank of Commerce, or BBC, was revealed to have made billions of dollars in questionable loans, including one to a convicted swindler known as “the Biscuit King”. BBC officials had papered over the bad loans, including using grossly overvalued property as collateral. The scandal, which led to the resignation of the country’s central bank government, hinted at the lax regulation, indebtedness and corruption at the heart of the Thai banking system.

Meanwhile in South Korea, in early 1997, a giant conglomerate called Hanbo Group went bankrupt, with about US$6 billion in debt.

The group’s chairman and son were convicted of using bank money to bribe regulators to stay quiet, and whispers began in Seoul about the fiscal health of the other large conglomerates.

But I, like many others, missed the significance of those two major events.

Instead, I was writing about the last British policemen on the Hong Kong force, the fate of the Gurkhas after the handover, whether the Vietnamese “boat people” would be resettled by July 1, and whether the old British cemetery in Happy Valley might be vandalised once Beijing took charge.

One of the biggest questions we in the media obsessed about was the future of Hong Kong’s elected legislature, which China vowed to abolish and replace with an appointed body.

The legislature was only partially democratic and relatively toothless. It was Governor Chris Patten’s last-minute attempt to inject a tiny dose of democracy into local politics before handing the colony and its 7 million inhabitants over to a Communist dictatorship.

But even that tiny dose was enough to rile Beijing, which colourfully labelled Patten a snake, a tango dancer and “a prostitute for a thousand generations”.

But Patten was right. He predicted Hongkongers would be terminally affected with the democracy bug. “You can dismantle institutions,” he said in one final interview, “but you can’t dismantle benchmarks.” Last year’s elections, with newcomers and pro-independence activists winning seats, proved a turning point in the city’s political development.

Trump’s media war: straight from the playbook of communist China

But the spectacle of the last British governor departing the empire’s last major colony – with Prince Charles on the royal yacht Britannia, no less – was too good a story to pass up. And it attracted thousands of journalists and camera crews from around the world, covering every backstreet and village of Hong Kong’s 2,754 sq km.

The bar at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club (where I served as president in 1997) was constantly thronged at night with visiting reporters and assorted hangers on. The venerable New York Post tabloid even commissioned an intrepid reporter to interview the Wan Chai bar girls for their views on whether the Communist takeover would be good or bad for the world’s oldest profession.

Hong Kong was the region’s Big Story. That is, until it wasn’t.