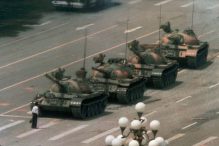

U.S. NEWS – Thirty years after government troops killed an unknown number of civilians, Beijing has astounded observers with the successful control of its people.

HONG KONG — In the three decades since the People’s Liberation Army staged its bloody 1989 massacre of pro-democracy students amassed at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, foreign journalists, human rights activists and outside observers of China have been confidently predicting two events likely to follow.

The first was an expected reversal of the official Communist Party verdict that labelled the Tiananmen Square protests as a “counterrevolutionary riot” and absolved the leaders who ordered the crackdown of any wrongdoing.

The second was the assured presumption that the next mass popular uprising was just a hair trigger away. The Tiananmen Square uprising and crackdown left a festering sore just beneath society’s surface. The next explosion of popular unrest, it was thought, would likely bring the end of the Chinese Communist Party’s rule.

In both cases, the haughty predictions have proven to be fallacies, expressions of hope over harsh reality. Thirty years after the soldiers brutally cleared the square on June 4, 1989, and as the party has moved to systematically erase the memory of the massacre from the history books and the collective memory, there has been no revisiting of the verdict, and no repeat uprising.

Instead, the Communist Party today looks as firmly entrenched in China as ever, Xi Jinping has emerged as the most powerful Chinese leader since perhaps Mao Zedong, and the uprising at Tiananmen Square seems ever more remote, an isolated, largely forgotten and increasingly irrelevant footnote in modern Chinese history.

How did that happen? And how did so many seasoned China watchers get it so wrong?

The reversal of the verdicts seemed the most likely, and was also the most widely predicted event which never happened.

There was precedent. After the violence and chaos of the Cultural Revolution, many of the party’s purged leaders including Deng Xiaoping, Zhao Ziyang and Hu Yaobang, were rehabilitated and returned to prominence. A 1981 Central Committee resolution acknowledged that the Cultural Revolution had brought “serious disaster and turmoil” to the country. Mao was deemed responsible for the chaos, and Deng later reassessed Mao as “70% good, 30% bad.”

Since China’s Communist Party has a history of acknowledging past mistakes, it seemed only natural that a new leadership team might want to assuage any lingering popular anger — and bolster their own legitimacy — by reversing the assessment of the Tiananmen protests.

A reversal would mean relabeling the students as patriotic, erasing the criminal records of the thousands sent to prisons or labor camps, and paying compensation to the families of those killed. That all seemed reasonable, with the passage of time.

That view was particularly prevalent in 2012, before Xi and his Number Two, Premier Li Keqiang, ascended to power. Li was especially seen as amenable to a reassessment of Tiananmen Square. After graduating from Peking University, Li became active with the Communist Youth League at the time pro-democracy sentiment was sweeping China’s campuses in the 1980s. Li was known to be friendly with some pro-democracy reformists who were later arrested and jailed for their part in the Tiananmen protests.

In 2012, several of those who knew Li from the 1980s confidently told me that he would be a voice for reform within the new leadership, and that a reversal of the official line on Tiananmen was only a matter of time.

Growing Unrest Across Country in the 21st Century

If the prediction of a reversal of verdicts was a fallacy, the idea that another Tiananmen-scale popular uprising was imminent also in retrospect seems hopelessly misplaced.

For a while, the notion did not appear so far-fetched. From the 1990s and into the 2000s, the number of impromptu outbursts of unrest across China rose steadily, reaching more than 100,000 a year by 2005. It seemed any one of them could be the spark that ignited a wider, nationwide conflagration.

There were thousands of scattered protests by farmers angry over the seizure of their land by unscrupulous developers in league with corrupt local officials. There were demonstrations by army veterans angry over inadequate benefits. Members of the quasi-religious group Falun Gong in 1999 staged the largest mass protest since Tiananmen Square, gathering an estimated 10,000 practitioners for a silent vigil outside Beijing’ central government leadership compound at Zhongnanhai.

In 2010, China was hit with a wave of labor unrest, including a strike at a Honda plant in Foshan that forced the temporary closure of four Honda assembly plants, and the suicides of at least 10 workers at a Foxconn electronics factory in Shenzhen. The following year saw an uprising in the village of Wukan in Guangdong Province, where villagers besieged a police station and forced the local Communist Party officials to flee to safety.

Hopes the Internet Would Spark a Revolt

At the same time, the period from 2009 to 2012 saw an explosion in the use of internet microblogging platforms, particularly Weibo, which led to a growing number of online protests that carried the potential of tipping from the virtual realm to the street.

Chinese internet users, known as “netizens,” began using their blogging sites to expose corruption by local officials and to decry instances of abuse by the rich and powerful against ordinary citizens. The so-called “princelings” — the newly wealthy children and grandchildren of China’s revolutionary elite — became particular targets of the online ire.

Even the party and its security apparatus were concerned about the fraying social fabric. After the start of the Arab Spring uprising in late 2010 and early 2011 — and amid rumors that shadowy overseas Chinese groups were trying to spark similar protests inside China — the party launched a sweeping crackdown, arresting bloggers, lawyers and dissidents such as the artist Ai Weiwei, shutting Weibo sites and stepping up its censorship regime. Even relatively mundane terms like “jasmine” became subject to censorship, because of possible references to the so-called “Jasmine Revolution” in the Middle East.

That China’s Communist Party was destined to face another Tiananmen-style “people power” revolt — with the internet as a mobilizing tool — for a time seemed not only plausible, but likely. This was, after all, the fate of other authoritarian regimes where an expanding urban middle class led to greater demands for democracy and openness — in the Philippines in 1986, in Taiwan, in South Korea, in 1998 in Indonesia.

Communist Rulers Adeptly Control the Public

But many of those foreign observers — myself included — failed to recognize several key factors that set China apart and that have given the Chinese Communist Party a durability that helped it defy the global trend toward more openness.

First, many saw but failed to appreciate the ability of China’s Communist Party to morph with the changing times. At the start of the internet and Weibo craze, the party appeared caught off guard. However, with time — and with Xi Jinping’s elevation to power at the 18th Party Congress — Beijing moved to gain control over the freewheeling web. Strict new regulations removed the anonymity of the Weibo-sphere. Well-known bloggers —known as the “Big Vs” — were more closely monitored, some shut down. Gradually, the open debates and conversations on Weibo shifted to closed private groups on WeChat.

The Party also learned to harness the internet for its own purposes. Weibo postings and comments became a way for the party to gauge and stay ahead of popular opinion. Party functionaries also began engaging in sophisticated public opinion polling operations on almost every topic, to identify any potential for dissent and address grievances in advance.

Second, China’s growing economy gave the party a bulwark against popular discontent. Elsewhere around the world, “people power” uprisings were fueled by falling living standards. China’s economy, even in the midst of a slowdown and a trade war with the United States, has still managed an enviable 6.3 percent growth each year.

Third, Chinese authorities have managed to construct what is arguably the world’s most sophisticated, most high-tech and most pervasive systems of population surveillance and control. From the ubiquitous security camera to facial recognition software to the new “social credit” scoring system, Chinese security officials can closely track virtually every citizen all the time.[

And finally, China’s Communist rulers have proven adept at playing the nationalist card. Any attack on the Communist Party becomes an attack on China itself, and an attempt to “contain” China’s unstoppable rise.

Fixation on Tiananmen Reaches into Hong Kong

Beijing’s leaders have also used the country’s economic clout to stoke patriotism abroad and force adherence to their preferred orthodoxy and lexicon. Thus, a 16-year old Taiwanese singer in an all-girl Korean K-pop band was forced to apologize for holding a Taiwanese flag during a performance. The Marriott Hotel chain had its website shut down and was forced to apologize for listing Hong Kong, Macau, Tibet and Taiwan as options for “country of residence” on a mundane survey. University professors in Australia have been pressured into apologizing for offending Chinese students.

The Chinese authorities’ obsession with preventing another Tiananmen Square is at the root of the mainland’s heavy-handed interference in Hong Kong. The 2014 pro-democracy Occupy protest, known as the “umbrella movement” in Hong Kong, was seen from Beijing as the greatest challenge to Chinese rule since the 1989 uprising.[

The harsh prison sentences handed down to the Occupy leaders, the disqualification from the local legislative council of young reform activists, even the pressure on Hong Kong authorities to enact strict new laws on respecting the Chinese national flag and anthem, and easing the way to transfer criminal suspects to the mainland for trial, all can be seen as Beijing’s attempt to prevent Hong Kong from becoming the next Tiananmen Square.

The Tiananmen Square protests 30 years ago ended in bloodshed, but for many foreign observers, the moment presaged that something bigger, and ultimately successful, was bound to reignite.

The Chinese Communist Party took the opposite lesson, and became determined never to let another Tiananmen Square happen again.

Originally published on: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2019-05-30/commentary-how-china-has-prevented-another-tiananmen?src=usn_tw